|

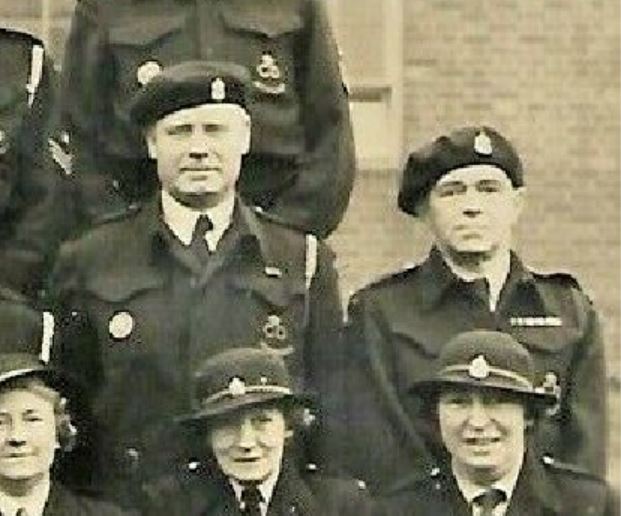

This is a pretty standard end of war 'stand down' photograph. The vast majority of civil defence personnel had these photos taken. There's nothing too surprising regarding insignia and uniforms but on the far right it looks like a gentleman has a different colour lanyard to the others. I've not seen this before and the colour may be a red lanyard whilst the others are old gold. I cannot determine the location from the area title alas.

0 Comments

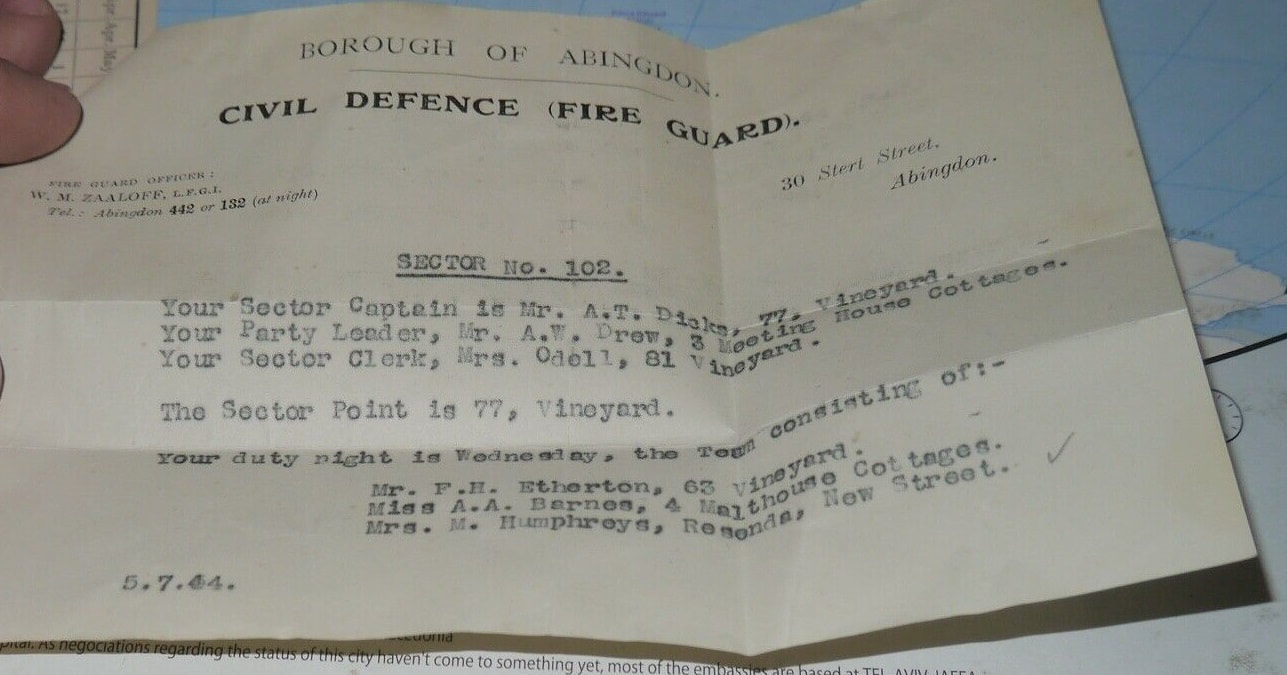

A small group of Fire Guard pose with a (small) trophy. Probably the winners of a local competition there is an interesting helmet marking on the chap bottom left. I'm unsure currently what the extra letters relate to. It looks like a P and an L. The gentleman bottom right does not seem at all pleased with the proceedings... Going by the information on this letter, the PL on the helmet almost certainly refers to "Party Leader". Seems there's quite a lot of hierarchy in the Fire Guard here - Sector Captain, Party Leader and then Sector Clerk.

This unique style of badge recently appeared among a selection of military badges for auction. I've not seen this style before and I'm uncertain exactly where it would have been worn, possibly on bluette overalls given the red lettering.

I've been receiving a number of emails requesting how someone may go about researching a member of their family who was an air raid warden or in other ARP and Civil Defence services. The key starting point is their local archive usually at the library (or sometimes called a local history centre, local studies centre or archives centre). The online starting point would be the 'Search local archives' website.

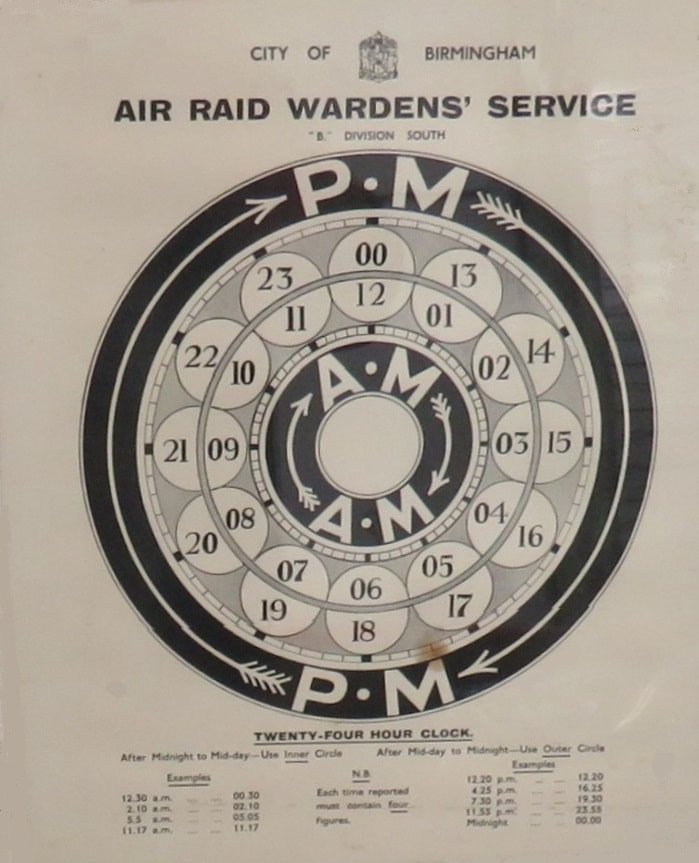

However, I have searched through a number of these in the London area and details about an individual who may have served are generally absent. Unless they were a senior member (along the lines of an Incident Officer) then it's unfortunately highly unlikely the archive will have much more detail than their name appearing on a list of wardens (but even that is difficult to come across). Finding details about an individual at these archives is therefore generally not going to happen. The archives do hold minutes of council meetings and some have letters from individuals but overall finding out about one person will not be possible. A few archives may have lists of wardens and the post they occupied but I have only seen one such list so far and it was for just a period in the summer of 1941. Some areas do have active local history groups that can assist research but again the likelihood of finding any detailed information on one person is unlikely. There is also the National Archives but their search engine often directs a user to the local archive. They hold numerous ARP and Civil Defence records but these are generally related to governmental business. An aide memoire for wardens not use to using the 24 hour clock.

|

Please support this website's running costs and keep it advert free

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

|

|

Copyright © 2018–2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed