|

In the London Civil Defence Region, senior supervisory positions within the Wardens’ Service wore white helmets with black bands front to rear (with space for a two-inch high "W" on the front and rear of the helmet). A Chief Warden wore a white helmet with two black bands, each one inch wide and placed ½ inch apart. The role of a District Warden (in London) or Divisional Warden (everywhere else after mid-1942) wore a single two-inch black band (although this was reduced to one inch later in 1942). The general rule was that the second in command would wear the same marking on their helmet as their boss, the idea was that if, for example, the Chief Warden wasn't present, the Deputy Chief Warden could be easily identified at an incident. It appears some Chief Wardens were not overly happy with this arrangement and their deputies were instructed to add "DEP." or "DEPUTY" above the "W". This would also cascade to the junior supervisory positions with the Deputy Head Warden having DH above the W or similar. Before standardisation was introduced across the country in mid-1942, outside of London senior ranks used one, two or three diamonds. Although an attempt was made to use the London marking across the whole country in the middle of 1942 it’s surprising how many helmets have survived bearing the rank diamonds. Thanks to Adrian Blake for the content idea. Adrian is co-author of "Helmets of the Home Front".

0 Comments

ARP Industrial Bulletin No.4 includes a section covering helmet markings (factories were to follow this outline but add their business name above the service letters, hence the slightly smaller height of the service letters at 1 and 1½ inches). As per Home Security Circular No. 139/1942 dated 9th July, 1942 a standard system of marking helmets for Civil Defence General Services under the control of Local Authorities was issued (it followed much of the standard set in London). Omitted from this list are the markings for Fire Services.

Service Lettering on Helmets

A recent blog from Adrian Blake posed the question about the many stories that have arisen about the use of non-metal helmets in ordnance factories during the second world war. Below is a letter from August 1940 detailing there was "...a proposal to supply women in munition factories with bakelite helmets."

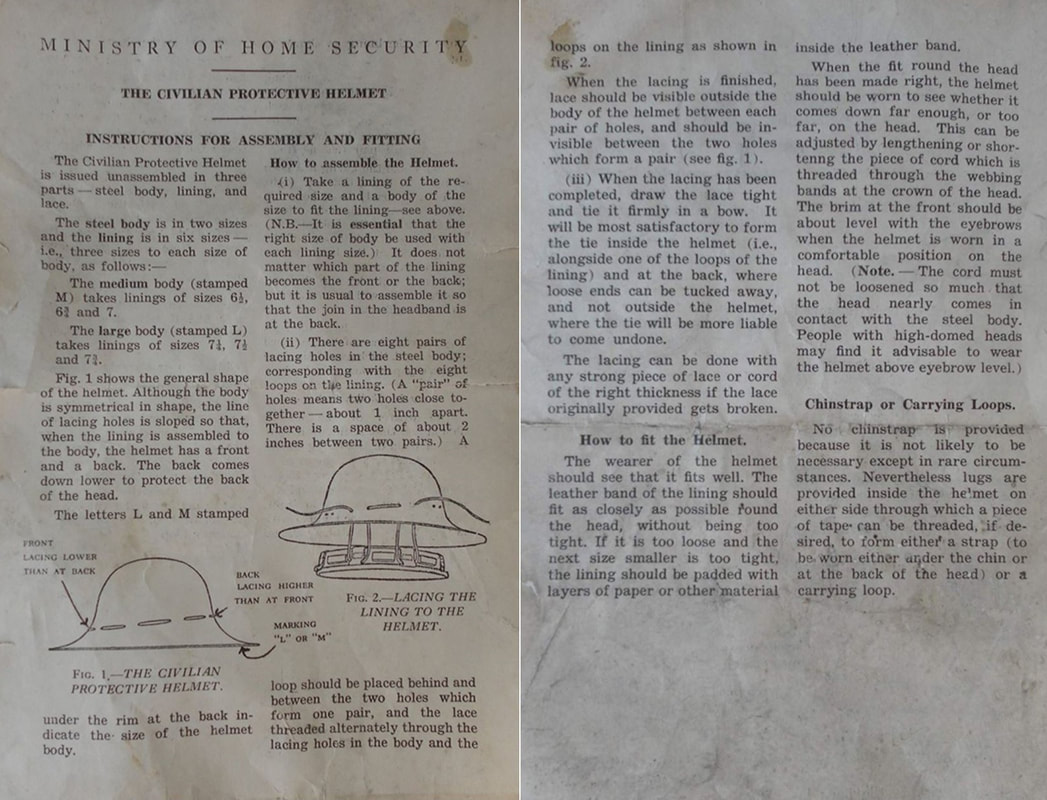

Unfortunately, we don't have any of the previous or follow-up letters about this. We don't know, for example, if a specific request had been made for non-metal helmets due to the risks of sparking accidents. However, it does highlight that non-metal helmets were being requested within ordnance factories. Other documents also mention the use of non-metal helmets being issued to war workers to wear during an air raid alert. They could wear a helmet whilst continuing to work until sent to the shelters. I imagine wearing a lighter helmet was a more comfortable option. This doesn't put to bed the myth of non-sparking helmets but it certainly adds more detail and opens further research opportunities. Thanks go to Chris Ransted for the image. The Civilian Protective Helmet (CPH) was designed specifically for use by civilians during the Second World War. The nickname – Zuckerman – was taken from one of its inventors, Solly Zuckerman (it remains uncertain if this name was used during the war years); the other designers were Hugh Cairns and Derman Christopherson. In October of 1940 the Ministry of Home Security noted the need for a new helmet for use by civilians. The CPH was chosen as the helmet to go in manufacture. The helmet was to be offered to the general public and businesses and the CPH would later became the main helmet issued to the Fire Guard Organisation of volunteer firefighters. Production commenced towards the end of 1940 and progressed into 1941 (though 1940-dated examples are much harder to find). The Treasury signed off on the expenditure of some £2,050,000 in November 1941 for the manufacture of a further 10,050,000 CPHs. The helmet was introduced in February 1941 (see publicity photo above) and general distribution appears to have commenced from mid-1941. Documents detail several names for the helmet being initially utilised: Industrial Helmet, Civilian Type Helmet, Alpine Helmet, Civilian Steel Helmet, New Protective Helmet, Civilian Grade 3, Steel Helmet-Home Security Pattern and of course ultimately the Civilian Protective Helmet. The high crown was designed to crumple under impact from falling debris. No chinstrap was issued (although two strap loops were fitted which differed in design across the manufacturers). A large number of manufacturers are seen on liners issued. The liner’s design and positioning were such that a chinstrap was not considered necessary (although several commercial chinstraps were for sale). The small holes in the brim, front and back, were used to run a wire through, holding piles of 10 helmets together for transit or storage. The holes around the crown were slightly angled enabling the helmet to sit lower at the rear. However, period photos often see the helmet worn back-to-front but it was more comfortable for the wearer (especially for women with a lot of hair). The helmet came in three parts: the shell, the liner (available in six sizes) and a lace to hold one to the other. The lace was threaded through the holes in the helmet and loops on the liner. It was a simple process that avoided the need to use helmet bolts and more expensive helmet liners. There was also an instruction leaflet on the assembly and fitting of the helmet. The helmets were made in two sizes either marked M (medium) or L (large) with three liners in different sizes for each helmet size. Several manufacturers received orders to produce the helmets causing different rims: rolled under, rolled up and a separate rim strip (the latter made by Rubery Owen).

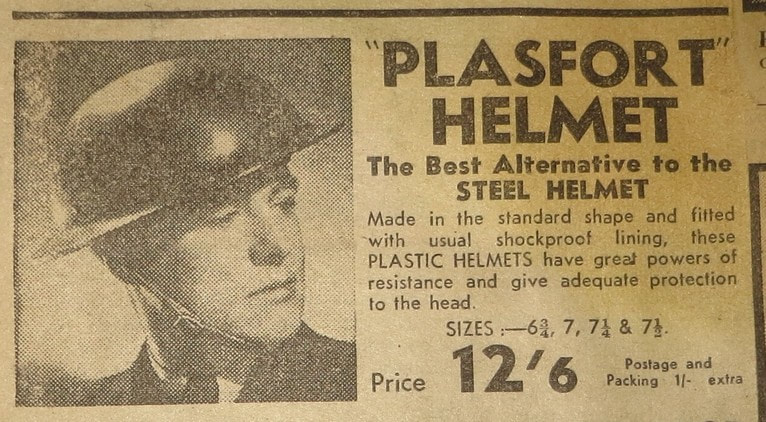

Distribution demands were enormous and records suggest that whilst manufacture commenced in 1941 it took until early to mid-1942 for the helmets to be finally issued. It was sold to the general public for five shillings and sixpence. The slow release was caused by issues over pricing, who should pay (businesses or their staff), ordering processes, transport, storage and prioritisation. CPHs were issued in one colour only – grey – but many were painted white with black bands added for ranks within the Fire Guard Organisation. Some helmets carry the names and logos of companies as part of their ARP commitment. A great number of CPHs can be found marked with “FG” (Fire Guard) or “SFP” (Street or Supplementary Fire Party). Before manufacture ceased some 10 million Civilian Protective Helmets had been produced. Archives also show that consideration was given to a CPH being used as a helmet and visor. Two eye holes were to be drilled 2½ inches apart above the brim and the helmet was to be pulled down over the forehead. This idea was discontinued as it was felt that the improved frontal protection left the rear of the head dangerously exposed. When the Government was looking at plastic as a possible helmet solution, experiments were undertaken with plastic CPHs and at one stage coloured plastics were even considered with pink being suggested “for the ladies”. The plastic CPHs did not progress when it became clear that the new production processes were slow and costly. To date, no examples of the coloured plastic test CPH models appear to have survived. Whilst the CPH is generally overlooked by helmet collectors it is regularly found on Second World War Home Front re-enactor displays. Overall, although not one of the best-looking helmets produced during the war, it no doubt saved many lives. I am obliged to Adrian Blake for content and Nigel Abram for the images. Guest blogger Adrian Blake asks a question about non-metal Home Front helmets. For nearly fifty years, I’ve been often told that non-metal Tommy-style helmets were specifically made for use in armaments factories. This is heard along the lines of ”they don’t spark you see” and were therefore safe to wear when working with explosives. The basis of this myth is this: if you were wearing your helmet when filling a large calibre shell, and your helmet somehow managed to fall off, and said helmet somehow managed to strike something metal and then send a spark from that strike into the explosive…you get the idea. I’ve met so many people who have been told by someone whose grandparents told them this story, but that’s not proof, it’s hearsay. The armaments factory slash non-metal helmet myth is now an oft-repeated mantra. So, the case is closed... or is it? Now, non-metal helmets were available in the early years of the Second World War such as the “Plasfort” or “Cromwell”. These brand names have become synonymous with almost any non-metal helmet of the period. For years I have been looking for proof that non-metal helmets were made specifically for the ordnance industries. However, to date, I’ve not seen any documents to support this claim.

The best I can say to support the argument is that it’s highly likely that non-metal helmets did find their way into hundreds of factories and that some of the factories may have been responsible for weapons manufacture. I’ve not yet found a single government memo or bulletin insisting that all workers must wear a non-metal helmet (be it plastic-, paper-, wood chip- or rag pulp-based). Let’s assume, for a moment, that the government didn’t commission any companies to manufacture non-metal helmets. Is it possible that several companies simply saw a gap in the market and decided to fill it? After Dunkirk, Britain had to use metal wisely to rebuild the Army and as a result, the government stopped all commercial sales of metal helmets to the public. Up to this point, anyone could have popped into a shop and bought themselves a tin helmet. Entrepreneurial firms were looking for uses for new materials and these ranged from Bakelite and other new plastics to what seemed to some like paper-mâché (wastepaper pulp mixed with glue and other additives). As a result, several Tommy-shaped head-protectors hit the market – some had product names like Plasfort and Cromwell whilst others are now unattributable to a specific manufacturer as they are completely unmarked. Advertisements were placed in newspapers and magazines stressing the strength and lightness of these new wonder materials and assuring buyers that the helmets could be easily decontaminated. But if non-conductivity and anti-sparking were key features of these exciting new products, that simply wasn’t being covered in the adverts. I’ve yet to see a single advert mention this. I’m beginning to wonder if non-metal helmets were just helmets for anyone and everyone. Manufacturers saw a market opportunity; they had products that they were constantly looking for extra applications for; they wanted additional income streams; and they had to take into consideration government sanctions. Surely, if the non-sparking helmet was a thing we’d see adverts for the new “Sparko-Stop” helmet or the exciting new “Anti-Electro-Helmet” wouldn’t we? I’ve seen period photographs of plastic helmets worn by smiling factory workers. But also by repair party workers, milkmen, shopkeepers even children but I’m keen to prove or disprove the myth behind these being primarily for ordnance workers. But who’s spreading and reinforcing this myth? I’m afraid it appears to be us: the collectors, the re-enactors, the dealers, the online sellers, the amateur historians. So there must be proof right? Why are we repeating this myth without evidence to support it? I think there’s a much more interesting fact-based narrative around these helmets than the current (unproven) non-sparking one. We know this was a period of new material development, we know these helmets were commercially-available items, we know they filled a gap when metal was scarce, we know how businesses work and we even know that Zuckerman helmets could have been made of plastic (there’s evidence of trials). So, there we go. If you have evidence (a document or an advert) to prove the myth behind the non-sparking helmet, please leave a comment. Please note: the leather Mark II-shaped helmet is a different kettle of fish altogether. |

Please support this website's running costs and keep it advert free

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

|

|

Copyright © 2018–2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed