|

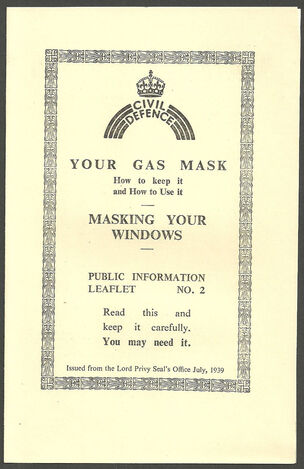

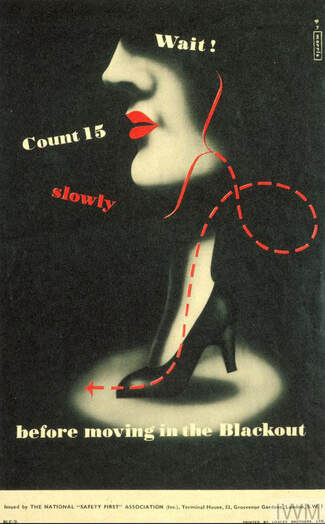

80 years ago today, on the 1 September 1939 (two days before war was declared), the British government introduced blackout restrictions. From the Lord Privy Seal's office this message was communicated: "A lighting order has been made under Defence Regulation No. 24 and comes into operation at sunset tonight as a further measure of precaution. The effect of the order is that every night from sunset to sunrise all lights inside buildings must be obscured and lights outside buildings must be extinguished, subject to certain exceptions in the case of external lighting where it is essential for the conduct of work of vital national importance. Such lights must be adequately shaded”. Every house, shop and factory was now under strict blackout rules. No light must escape from any source including from car headlamps. Preparations for the blackout had been taking place for years previously. The recruitment of ARP wardens had begun in March 1937 when the Home Office sought to recruit 300,000 volunteers (take up was initially slow but as the threat of war increased numbers grew). Trials of the blackout had started in 1938 and the crises in Europe intensified. The government also sent every household a number of information leaflets in 1939; leaflet number two covered the requirements for the blackout with details on masking windows. During the previous couple of years the Air Ministry had reviewed how bombers may attack the UK. They thought that bombers would primarily attack at night. To counter this threat they advised the extinguishing all ground light sources would hamper the navigation of enemy bombers and affect the accuracy of their bombing. To ensure no light escaped every house was expected to place heavy cotton fabric or brown paper over every window to stop light creeping out (or paint windows or place cardboard or wood panels over the windows). Preparing a house each evening for the blackout soon became a chore. And with no air raids happening people quickly tired of the process and also of the ARP wardens who enforced the regulations. With fines for those breaking the blackout, wardens soon became the bane of many households. Newspapers published that day's blackout times which would be 30 minutes after sunset and 30 minutes before sunrise. For shops and pubs, the need for customers to leave their premises without light escaping led to the introduction of double curtained entrances. Somewhat cumbersome and expensive to deploy. In factories, the same blackout regulations were enforced. Many businesses permanently covered windows and skylights which led to increased use of interior lighting at all hours. The impact of this was both expensive in extra electricity consumption and also a lowering of employee morale due to the lack of natural light in the day. For car drivers the blackout became a motoring nightmare. No interior lights were to be shown and only one headlamp could be used, pointing immediately downwards, which also had to have a special housing to limit the amount of light (introduced in 1940). Indicators and rear brake and running lights also had to be dimmed and screened. The immediate impact of the blackout was a dramatic rise in car collisions and pedestrian accidents. Over a thousand people had been killed on the roads of the first month of implementation. By early 1940 handheld torches were allowed but batteries became scarce and expensive to obtain. The speed limit during the blackout was also lowered to 20 mph. White lines were painted on the roads and also on kerbs, telephone kiosks and post boxes. A number of business sold items that claimed to be luminous (badges and armbands) which would aid people in the dark, but in reality their usefulness was extremely limited. The blackout also saw a large rise in reported crime - from muggings, looting and burglary to assaults and murders.

The Ministry for Home Security issued a plethora of posters and leaflets to inform the public how to better navigate in the blackout. These included how to hail a bus in the dark with their torch to taking extreme care when exiting from a train carriage. As elsewhere all train carriages were screened and accidents at railway stations rocketed. Blackout restrictions were not eased until September 1944 when the dim-out was introduced. Lighting equivalent to that on a clear full moon night was allowed but had to be extinguished if an air raid alert was sounded. It was not until April 1945 that full street lighting returned to Britain - in London this was symbolically started with the lighting of the four clock faces on Big Ben on 30 April 1945.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Please support this website's running costs and keep it advert free

Categories

All

Archives

June 2024

|

|

|

Copyright © 2018–2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed